Novel

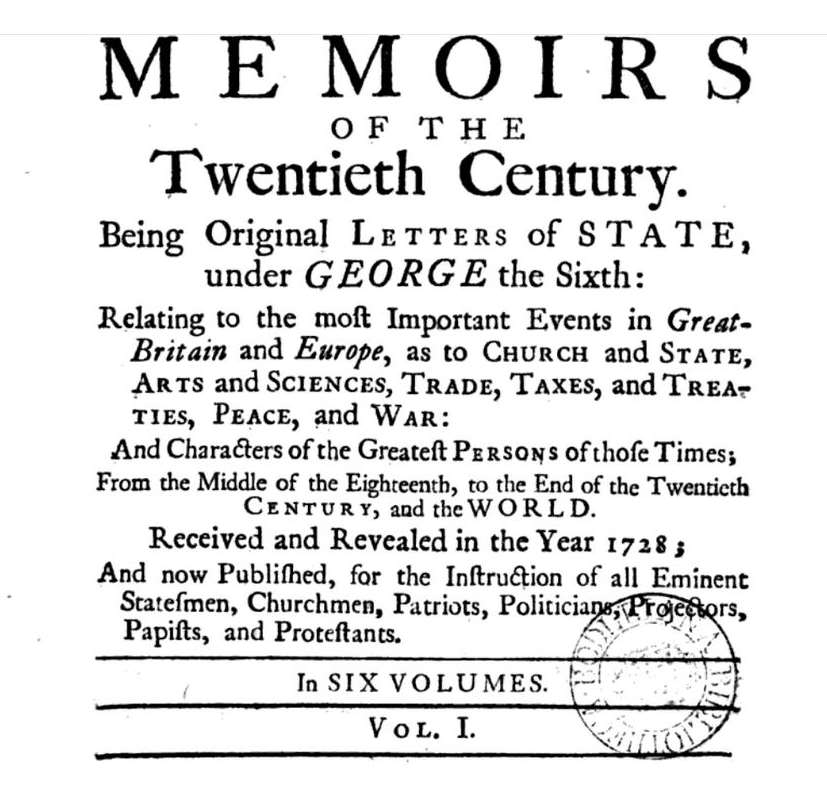

Memoirs of the Twentieth Century

- by Samuel Madden

- (Osborn and Longman, March 1733)

A group of letters from the late 20th century found their way to Samuel Madden, who rushed to publish them in this volume, but then destroyed most of the copies.

I found this account of Madden’s book in Googlebooks scanned copy of the work. The note is attributed to Anecdotes of the Life of Mr. Wm. Bowyer:

In her Ph.D. dissertation, Dierdre Ní Chuanacháin suggests that the reason for the suppression was the “ politicaland literary milieu” of the times. Nevertheless, at least one copy of the work survived and is hailed as the first literary work to actually write of the future (albeit as a satire and criticism of 18th century Great Britain) and possibly the first to contain time travel (via an unexplained method). Those two aspects led us to classify the work as a forerunner of science fiction. —Michael Main

I found this account of Madden’s book in Googlebooks scanned copy of the work. The note is attributed to Anecdotes of the Life of Mr. Wm. Bowyer:

There is something mysterious in the History of this Work; it was written by Dr. Samuel Madden, Patriot of Ireland; & addressed in an Ironical Dedication, [to] Frederick Prince of Wales. One Volume only of these Memoirs appeared, and whether any more were really intended is uncertain. A Thousand Copies were printed, with such very great dispatch that three Printers were employed on it (Bowyer, Woodfall, & Roberts,) but the whole of the Business was transacted by Bowyer, without either of the other Printers ever seeing the Author: and the Names of an uncommon number of reputable Booksellers appeared in the Title Page. The Book was finished at the Press on March 24th 17323 and 100 Copies were that day delivered to the Author: on the 29th a number of them was delivered to the several Booksellers mentioned in the Title Page: and in four days after, all that were unsold, amounting to 890 of these Copies, were recalled, and were delivered to Dr. Madden, to be destroyed. The current report is, that the Edition was suppressed on the day of publication: and that it is now exceeding scarce is certain. The reasons for the extraordinary circumstances attending the printing and suppressing These Memoirs, are not very evident, and still remain a Mystery.

In her Ph.D. dissertation, Dierdre Ní Chuanacháin suggests that the reason for the suppression was the “ politicaland literary milieu” of the times. Nevertheless, at least one copy of the work survived and is hailed as the first literary work to actually write of the future (albeit as a satire and criticism of 18th century Great Britain) and possibly the first to contain time travel (via an unexplained method). Those two aspects led us to classify the work as a forerunner of science fiction. —Michael Main

But as I am determined to give ſuch Readers and all Men, ſo full, and fair, and convincing an Account of my ſelf and that celeſtial Spirit I receiv’d theſe Papers from, and to anſwer all Objections ſo entirely, as to put Ignorance, and even Malice it ſelf to Silence: I am confident, the ingenuous and candid part of the World, will ſoon throw off ſuch mean narrow ſpirited Suſpicions, as unjuſt and ungenerous.