Cited in Worlds Enough and Time, edited by Gary Westfahl

Tag Area: Reference Work

- Filter: Show all works, including those with no time phenomena.

- Found: 299 results in 7.72ms

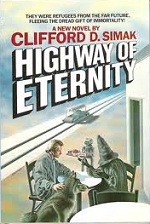

Novel

Novel

Novella

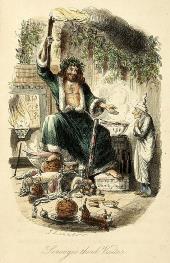

A Christmas Carol

- by Charles Dickens

- (Chapman and Hall, December 1843)

According to my Grandpa Main’s notes (which formed the basis of the first version of the ITTDB), he struggled with what he called the Carol Question as long ago as 1916. Is there actual travel through time in “A Christmas Carol” or not? It’s easy to see why the Carol Question is central to the ITTDB. On the one hand, Scrooge does take a clear trip to the past:

Now if that’s not time travel, what is? Ah . . . “Not so fast!” says Ghost!

Even Ghost Himself admits there’s no interaction with the past. Observation is permitted, but not interaction. They might as well be watching a movie! In general, if you can’t interact with the past and the past can’t see you, then there’s no actual time travel!

Fair enough, but what about Future Ghost? Isn’t He bringing information from the future to Scrooge? Transfer of information from the future to the past may be boring compared to people-jumping, but it is time travel, so the Carol must be granted membership in the list after all, don’t you think? Ah, not so fast again! At one point, Scrooge asks a pertinent question:

The answer is critical to whether time travel occurs. The difference between things that May Be and things that Will Be is like the difference between Damon Knight and Doris Day: Both are quite creative, but (as far as I know) there’s only one you go to for a rousing time travel yarn. Future Ghost never clear answers the question, and moreover, Scrooge appears intent on not having the future he sees come true. So, I want to say that Scrooge saw only a prediction or a prophecy or a vision of a possible future—which is, at best, debatable time travel.

Thus speaketh the ITTDB.

—Michael Main

They walked along the road, Scrooge recognising every gate, and post, and tree; until a little market-town appeared in the distance, with its bridge, its church, and winding river. Some shaggy ponies now were seen trotting towards them with boys upon their backs, who called to other boys in country gigs and carts, driven by farmers. All these boys were in great spirits, and shouted to each other, until the broad fields were so full of merry music, that the crisp air laughed to hear it!

Now if that’s not time travel, what is? Ah . . . “Not so fast!” says Ghost!

“These are but shadows of the things that have been,” said the Ghost. “They have no consciousness of us.”

Even Ghost Himself admits there’s no interaction with the past. Observation is permitted, but not interaction. They might as well be watching a movie! In general, if you can’t interact with the past and the past can’t see you, then there’s no actual time travel!

Fair enough, but what about Future Ghost? Isn’t He bringing information from the future to Scrooge? Transfer of information from the future to the past may be boring compared to people-jumping, but it is time travel, so the Carol must be granted membership in the list after all, don’t you think? Ah, not so fast again! At one point, Scrooge asks a pertinent question:

“Before I draw nearer to that stone to which you point,” said Scrooge, “answer me one question. Are these the shadows of the things that Will be, or are they shadows of things that May be, only?”

The answer is critical to whether time travel occurs. The difference between things that May Be and things that Will Be is like the difference between Damon Knight and Doris Day: Both are quite creative, but (as far as I know) there’s only one you go to for a rousing time travel yarn. Future Ghost never clear answers the question, and moreover, Scrooge appears intent on not having the future he sees come true. So, I want to say that Scrooge saw only a prediction or a prophecy or a vision of a possible future—which is, at best, debatable time travel.

Thus speaketh the ITTDB.

—Michael Main

If these shadows remain unaltered by the Future, the child will die.

Short Story

Mellonta Tauta

- by Edgar Allan Poe

- in Godey’s Lady’s Book, February 1849

So just how did those letters from the year 2848 make their way back to Poe if not for time travel? —Michael Main

To the Editors of the Lady’s Book:—

I have the honor of sending you, for your magazine, an article which I hope you will be able to comprehend rather more distinctly than I do myself. It is a translation, by my friend, Martin Van Buren Mavis, (sometimes called the “Toughkeepsie Seer,”) of an odd-looking MS. which I found, about a year ago, tightly corked up in a jug floating in the Mare Tenebrarum—a sea well described by the Nubian geographer, but seldom visited now-a-days, except for the transcendentalists and divers for crotchets.

Short Story

The Clock That Went Backward

- by Edward Page Mitchell

- New York Sun, 18 September 1881

A young man and his cousin inherit a clock that takes them back to the siege of Leyden at the start of October 1574, where they affect that time as much as it has affected them. This is travel in a machine (or at least an artifact), but they have no control over the destination. —Michael Main

The hands were whirling around the dial from right to left with inconceivable rapidity. In this whirl we ourselves seemed to be borne along. Eternities seemed to contract into minutes while lifetimes were thrown off at every tick.

Novel

Looking Backward from 2000 to 1887

- by Edward Bellamy

- (Ticknor, 1888)

As with The Diothas from earlier in the same decade, our hero tells the story of a man (Julian West) who undergoes hypnotically induced time travel, this time to the year 2000 and a socialist utopian society. —Michael Main

It would have been reason enough, had there been no other, for abolishing money, that its possession was no indication of rightful title to it. In the hands of the man who had stolen it or murdered for it, it was as good as in those which had earned it by industry. People nowadays interchange gifts and favors out of friendship, but buying and selling is considered absolutely inconsistent with the mutual benevolence and disinterestedness which should prevail between citizens and the sense of community of interest which supports our social system. According to our ideas, buying and selling is essentially anti-social in all its tendencies. It is an education in self-seeking at the expense of others, and no society whose citizens are trained in such a school can possibly rise above a very low grade of civilization.

Novel

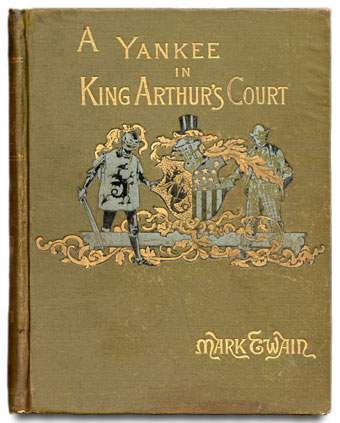

A Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

- by Mark Twain

- (Charles L. Webster, 1889)

A clonk on the head transports Hank Morgan from the 19th century back to the time of Camelot. We classify Yankee as science fiction not because of its clonk-on-the-head method of time travel, but rather for Hank’s dogged desire to bring modern technology to the Middle Ages. —Michael Main

You know about transmigration of souls; do you know about transportation of epochs—and bodies?

Novel

Sylvie and Bruno

- by Lewis Carroll

- (Macmillan, December 1889)

Alice told us, “I can’t go back to yesterday because I was a different person then.” But Lewis Carroll’s lesser known characters have no such injunction against time traveling. Near the end of the first volume of Sylvie and Bruno, the Professor—who is a sometimes tutor for the royal children Sylvie and Bruno—produces his Outlandish watch that controls time and permits backward time travel up to a full month.

Alas, the Outlandish watch doesn’t play much of a role in the story. Lewis Carroll tries to use it to avert a bicycle accident, and indeed the accident is annihilated, but only temporarily until the time when the watch was first set backward reoccurs. At that point, all is once again as it was with the bicyclist in a lump on the ground. —Michael Main

Alas, the Outlandish watch doesn’t play much of a role in the story. Lewis Carroll tries to use it to avert a bicycle accident, and indeed the accident is annihilated, but only temporarily until the time when the watch was first set backward reoccurs. At that point, all is once again as it was with the bicyclist in a lump on the ground. —Michael Main

“It goes, of course, at the usual rate. Only the time has to go with it. Hence, if I move the hands, I change the time. To move them forwards, in advance of the true time, is impossible: but I can move them as much as a month backwards—that is the limit. And then you have the events all over again—with any alterations experience may suggest.”

“What a blessing such a watch would be,” I thought, “in real life! To be able to unsay some heedless word—to undo some reckless deed! Might I see the thing done?”

“With pleasure!” said the good natured Professor. “When I move this hand back to here,” pointing out the place, “History goes back fifteen minutes!”

Novel

News from Nowhere

- by William Morris

- 39-part serial, The Commonweal, 11 January 1890 to 4 October 1890

Via a dream, the “Guest”—most likely Morris himself—travels a century or more into the future where he finds an almost communistic society working smoothly. —based on Frank J. Bleiler

The date shut my mouth as if a key had been turned in a padlock fixed to my lips; for I saw that something inexplicable had happened, and that if I said much I should be mixed up in a game of cross questions and crooked answers.

Novel

Novel

The Time Machine

- by H. G. Wells

- serialized in New Review, (five parts, January to May 1895)

In which H. G. Wells’s third foray into time travel finalizes the story of our favorite unnamed Traveller and his machine, all in the form that we know and love.

The two earlier forays were The Chronic Argonaut (which was abandoned after three installments in his school magazine) and seven fictionalized National Observer essays (which sketched out the Traveller and his machine, including a glimpse of the future and proto-Morlocks). The story of The Time Machine itself had three 1895 iterations:

[ul]

[li]A five-part serial in the January through May issues of New Review, The serial contains mostly the story as we know it, but with an alternate chunk in the introduction where the Traveller discusses free will, predestination, and a Laplacian determinism of the universe.

In addition, material from Chapter XIII of the serial (just over a thousand words beginning partway through the first paragraph of page 577 and continuing to page 579, line 29) were omitted from later editions. This section was written for the serial after a back-and-forth written struggle between Wells and New Review editor William Henley. The material had a separate mimeographed publication by fan and Futurian Robert W. Lowndes in 1940 as “The Final Men” and has since had multiple publications elsewhere with varying titles such as “The Gray Man.”[/li]

[li]The US edition: The Time Machine: An Invention, by H. G. Wells (erroneously credited as H. S. Wells in the first release), Henry Holt [publisher], May 1895. This edition may have been completed before the serial, as it varies from the serial more so than the UK edition. It does not contain the extra material in the first chapter or “The Final Men” (although it does have a few additional sentences at that point of Chapter XIII).[/li]

[li]The UK edition: The Time Machine: An Invention,by H. G. Wells, William Heinemann [publisher], May 1895. This edition is a close match to the serial, with the exception of chapter breaks, the extra material in the first chapter, and “The Final Men” (omitted from what is now Chapter XIV).[/li]

[/ul]

—Michael Main

The two earlier forays were The Chronic Argonaut (which was abandoned after three installments in his school magazine) and seven fictionalized National Observer essays (which sketched out the Traveller and his machine, including a glimpse of the future and proto-Morlocks). The story of The Time Machine itself had three 1895 iterations:

[ul]

[li]A five-part serial in the January through May issues of New Review, The serial contains mostly the story as we know it, but with an alternate chunk in the introduction where the Traveller discusses free will, predestination, and a Laplacian determinism of the universe.

In addition, material from Chapter XIII of the serial (just over a thousand words beginning partway through the first paragraph of page 577 and continuing to page 579, line 29) were omitted from later editions. This section was written for the serial after a back-and-forth written struggle between Wells and New Review editor William Henley. The material had a separate mimeographed publication by fan and Futurian Robert W. Lowndes in 1940 as “The Final Men” and has since had multiple publications elsewhere with varying titles such as “The Gray Man.”[/li]

[li]The US edition: The Time Machine: An Invention, by H. G. Wells (erroneously credited as H. S. Wells in the first release), Henry Holt [publisher], May 1895. This edition may have been completed before the serial, as it varies from the serial more so than the UK edition. It does not contain the extra material in the first chapter or “The Final Men” (although it does have a few additional sentences at that point of Chapter XIII).[/li]

[li]The UK edition: The Time Machine: An Invention,by H. G. Wells, William Heinemann [publisher], May 1895. This edition is a close match to the serial, with the exception of chapter breaks, the extra material in the first chapter, and “The Final Men” (omitted from what is now Chapter XIV).[/li]

[/ul]

—Michael Main

I drew a breath, set my teeth, gripped the starting lever with both hands, and went off with a thud.

Short Story

Novel

Short Story

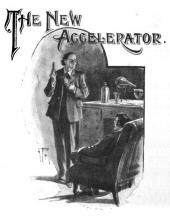

The New Accelerator

- by H. G. Wells

- Strand Magazine, December 1901

The narrator and Professor Gibberne test the professor’s potion that will speed up their metabolisms by a factor of a thousand or more. —Michael Main

I sat down. “Give me the potion,” I said. “If the worst comes to the worst it will save having my hair cut, and that I think is one of the most hateful duties of a civilized man. How do you take the mixture?”

Novel

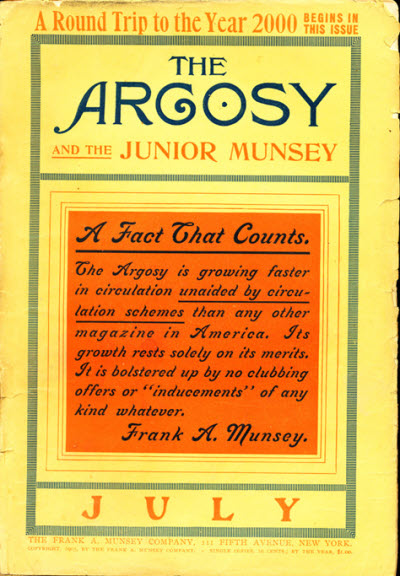

A Round Trip to the Year 2000; or a Flight through Time

- by W. W. Cook

- serialized in Argosy, July to October 1903

Pursued by Detective Klinch, Everson Lumley takes up Dr. Alonzo Kelpie’s offer to whisk him off to the year 2000 (in his time-coupé) where Lumley first observes various scientific marvels and then realizes that Klinch is still chasing him through time and into more adventures. All that, and there’s also a 1913 sequel!

William Wallace Cook’s larger claim to fame might be his 1928 aid to writers of all ilk: Plotto: The Master Book of All (1,462) Plots. —Michael Main

William Wallace Cook’s larger claim to fame might be his 1928 aid to writers of all ilk: Plotto: The Master Book of All (1,462) Plots. —Michael Main

Although your enemy is within a dozen feet of you, Lumley, he will soon be a whole century behind, and you will be safe.

Novel

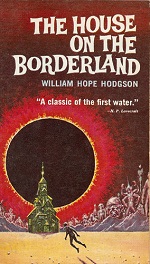

The House on the Borderland

- by William Hope Hodgson

- (Chapman and Hall, 1908)

Supernatural-story pioneer William Hope Hodgson was an inspiration for Lovecraft and later generations of writers. This novel of an Irish house that lay at the intersection of monstrous other dimensions seems to include time travel when the narrator witnesses and returns from a future the Earth is falling into the Sun while a second green star visits our solar system. —Michael Main

Years appeared to pass, slowly. The earth had almost reached the center of the sun’s disk. The light from the Green Sun—as now it must be called—shone through the interstices, that gapped the mouldered walls of the old house, giving them the appearance of being wrapped in green flames. The Swine-creatures still crawled about the walls.

Novel

Novel

The Worm Ouroboros

- by E. R. Eddison

- (Jonathan Cape, 1922)

For the most part, the story is a high fantasy in which three chiefs of Demonland—Lord Juss, Spitfire, and Brandoch Daha—embark on a heroic quest to rescue the fourth lord from his imprisonment in the mountains of Impland. However, at the end, Queen Sophonisba undertakes a resolution to the final problem that could well involve time travel. —Michael Main

Lord, it is an Ambassador from Witchland and his train. He craveth present audience."

Short Story

Novel

The Burning Ring

- by Katharine Burdekin

- (Thornton Butterworth, 1927)

In the decade before Tolkien, Derbyshire author Katharine Burdekin wrote of young Robert Carling who had a magic ring of his own, a ring that took him to ancient Rome, the age of Charles II, and the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

Novella

Short Story

The Shadow Girl

- by Ray Cummings

- in Argosy, 22 June to 13 July 1929

In the year 7012 A.D., scientist Poul and his beautiful (shadowy) granddaughter Lea construct a tall tower that can travel throughout time in the area that is presently Central Park in New York City, but an evil mimic creates his own tower from which he conducts time raids (most often involving Lea), and counter-raids ensue.

Lea is but one of the prolific Cummings’s many girls! You can also have the Girl in the Golden Atom, the Sea Girl, the Snow Girl, the Gadget Girl, the Thought Girl, the Girl from Infinite Smallness, and the Onslaught of the Druid Girls.

Lea is but one of the prolific Cummings’s many girls! You can also have the Girl in the Golden Atom, the Sea Girl, the Snow Girl, the Gadget Girl, the Thought Girl, the Girl from Infinite Smallness, and the Onslaught of the Druid Girls.

No vision this! Reality! Empty space, two moments ago. Then a phantom, a moment ago. But a real tower, now! Solid. As real, as existent—now—as these rocks, these trees!

Novel

Last and First Men

- by Olaf Stapledon

- (Methuen, 1930)

Time travel plays only a tiny role in this classic story of the history of men over the coming two billion years—in that the story itself is transmitted through time into the brain of a 20th century writer.

This book has two authors, one contemporary with its readers, the other an inhabitant of an age which they would call the distant future. The brain that conceives and writes these sentences lives in the time of Einstein. Yet I, the true inspirer of this book, I who have begotten it upon that brain, I who influence that primitive being's conception, inhabit an age which, for Einstein, lies in the very remote future.

Feature Film

Just Imagine

- by B. G. De Sylva, Lew Brown, and Ray Henderson, directed by David Butler

- (at movie theaters, USA, 23 November 1930)

Long before there was R2D2, there were RT-42, J-21, and other humans zipping around in their 1980s-era flying cars, racing off to Mars in their personal rockets, and waking a man named Peterson (or, as they say, “Single O”) who was struck down by lightning fifty years earlier. Alas, this is just a long-sleep story, but still worth listing for its historical value. —Michael Main

Well, her boss, Dr. X-10, is trying to bring a man to life who’s been dead fifty years!

Short Story

Feature Film

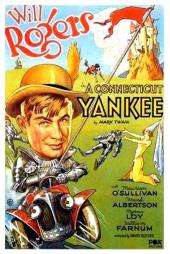

A Connecticut Yankee

- by William M. Conselman, Owen Davis, and Jack Moffitt, directed by David Butler

- (at movie theaters, USA, 6 April 1931)

This version of Twain’s story borrows some sf tropes from Shelley’s Frankenstein (a mad scientist) and Kipling’s “Wireless” (recovering sound from the past), although all that is small potatoes next to Will Rogers’ folksy wit. His character—Hank “Martin—is tossed back to Camelot when a bolt of lightning and a suit of armor knock him over at the mad scientist’s lab, and at the end, he returns via a similar timeslip. In between, we get one-liners, tommy guns, tanks, cars, characters that are eerily familiar from Martin’s present-day life—and a lot of time to debate whether this version has a real timeslip or is just a dream. —Michael Main

Think! Think of hearing Lincoln’s own voice delivering the Gettysburg address!

Novel

The Time Stream

- by [Error: Missing ':]' tag for wikilink]

- in Wonder Stories, December 1931 to Mar 1932

In this dated sf classic, four like-minded men from 1906 are swept into the time stream via a mental exercise, taken to the land of Eos in a far-off time (possibly in the past, possibly in the future) where they encounter Cheryl (who may or may not be the Cheryl that they know in their own time) and consider how personal freedom may or may not be abrogated.

No man or woman of Eos has the authority to direct, check, or in any way influence the free decision and impulses of another without that other’s full and intelligent consent. We demand the right to follow the natural inclinations of our characters. We demand the right to marry.

Novelette

Poem

The End of the World

- by Ralph Milne Farley

- Science Fiction Digest, July 1933 [Fanzine.]

An homage to Wells’ time traveler ”at the farthest forward point in time to which he penetrated.” —based on an author’s introduction

Feature Film

Berkeley Square

- by Sonya Levien and John L. Balderston, directed by Frank Lloyd

- (premiered at an unknown movie theater, New York City, 13 September 1933)

Leslie Howard reprises his dual role of two Peter Standishes from the 1929 Broadway stage performance of Balderston’s Berkeley Square, which in turn was loosely based on Henry James’s unfinished novel The Sense of the Past. The timeslips result in 18th-century Peter exchanging places with his 20th-century version, and they occur via thunderstorms and an overpowering belief by present-day Peter that the house and a diary he found there are somehow calling him to the past. —Michael Main

I believe that when I go back to my house at Berkeley Square at half past five tonight, I shall walk straight into the 18th century and meet the people living there.

Novella

Sidewise in Time

- by Murray Leinster

- in Astounding Stories, June 1934

Leinster’s title provides hope that this could be an early story of mixed-era geography, and indeed, the world of the story does have seemingly different times adjacent to each other. But we soon find out that these different times are actually the result of alternative histories that have been played out to the twentieth century and then appeared in different geographic areas. Yep! The Norse settled the Americas! The South won the war! The dinosaurs never died! And they're all next door to pompous Professor Minott and his merry band of students. —Michael Main

There are an indefinite nubmer of possible futures, any one of which we would encounter if we took the proper ‘forks” in time.

Short Story

Twilight

- by John W. Campbell, Jr.

- Astounding Stories, November 1934

In 1932, James Waters Bendell picks up a magnificently sculpted hitchhiker named Ares Sen Kenlin (the Sen means he’s a scientist, but Waters is just a name) who says that he’s trying to get back to his home time (3059) after beding pulled into a far distant future where mankind has atrophied because of their reliance on machines. —Jeff Delgado

They stand about, little misshapen men with huge heads. But their heads contain only brains. They had machines that could think—but somebody turned them off a long time ago, and no one knew how to start them again. That was the trouble with them. They had wonderful brains. Far better than yours or mine. But it must have been millions of years ago when they were turned off, too, and they just hadn’t thought since then. Kindly little people.

Short Story

Alas, All Thinking

- by Harry Bates

- Astounding, June 1935

Charles Wayland is tasked with discovering why his cold-hearted college buddy and all-around genius (I.Q. 248) physicist Harlan T. Frick has abandoned everything technical for mundane pursuits such as golfing, clothes, travel, fishing, night clubs, and so on—and the explanation may have to do with either Humpty Dumpty or Frick’s trip to the future with an average (but meditative) young woman named Pearl who is most curious about love.

I showed her New York. She’d say, “But why do the people hurry so? Is it really necessary for all those automobiles to keep going and coming? Do the people like to live in layers? If the United States is as big as you say it is, why do you build such high buildings? What is your reason for having so few people rich, so many people poor?” It was like that. And endless.

Short Story

Night

- by John W. Campbell, Jr.

- Astounding, October 1935

Bob Carter takes a plane up to 45,000 feet to test an anti-gravity device, but instead it hurls him into the same future as the story “Twilight”—but whereas the earlier story had mankind who were dying out in 7,000,000 A.D. because of the ubiquity of machines, Carter finds himself billions of years beyond that, with both man and (most) machines long gone.

Ah, yes, you have a mathematical means of expression, but no understanding of that time, so it is useless. But the last of humanity was allowed to end before the Sun changed from the original G-O stage—a very, very long time ago.

Short Story

The Shadow Out of Time

- by H. P. Lovecraft

- Astounding, June 1936

During an economics lecture, Professor Nathaniel Wingate Peaslee’s body and mind are taken over by a being who can travel to any time and place of his choice, and during the next five years the being studies us, all of which Peaslee pieces together after his return.

Lovecraft scholar S.T. Joshi says that Lovecraft saw the movie Berkeley Square four times in 1933, and “its portrayal of a man of the 20th century who somehow merges his personality with that of his 18th-century ancestor” served as Lovecraft’s inspiration for this story.

Lovecraft scholar S.T. Joshi says that Lovecraft saw the movie Berkeley Square four times in 1933, and “its portrayal of a man of the 20th century who somehow merges his personality with that of his 18th-century ancestor” served as Lovecraft’s inspiration for this story.

The projected mind, in the body of the organism of the future, would then pose as a member of the race whose outward form it wore, learning as quickly as possible all that could be learned of the chosen age and its massed information and techniques.

Novel

Play

Short Story

Short Story

Novel

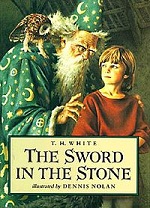

The Once and Future King

- by T. H. White

- (1938)

Merlyn, who experiences time backward, is the traveler in this series, which was introduced to me by Denbigh Starkey, my undergraduate advisor at WSU and later a member of my Ph.D. committee.

The first four short books in the series were collected (with a substantial cut and revision to #2) into a single volume, The Once and Future King, in 1958. A final part, The Book of Merlyn written in 1941, was published posthumously in 1971.

The first four short books in the series were collected (with a substantial cut and revision to #2) into a single volume, The Once and Future King, in 1958. A final part, The Book of Merlyn written in 1941, was published posthumously in 1971.

- The Sword in the Stone, 1938 —Arthur is crowned

- The Witch in the Wood, 1939, aka The Queen of Air and Darkness (cut and revised), 1958 —young King Arthur

- The Ill-Made Knight (1940)—Sir Lancelot

- The Candle in the Wind (1958)—the end of Camelot

- The Book of Merlyn (1977)—the final battle with Mordred

EVERYTHING NOT FORBIDDEN IS COMPULSORY.

Novel

The Legion of Time

- by Jack Williamson

- serialized in Astounding Science Fiction, May to July 1938

After two beautiful women of two different possible futures appear to physicist Denny Lanning, he finds himself swept up by a time-traveling ship, the Chronion, along with a band of fighting men who swear their allegiance to The Legion of Time and its mission to ensure that the eviler of the two beautiful women never comes to pass.

But Max Planck with the quantum theory, de Broglie and Schroedinger with the wave mechanics, Heisenberg with matrix mechanics, enormously complicated the structure of the universe—and with it the problem of Time.

With the substitution of waves of probability for concrete particles, the world lines of objects are no longer the fixed and simple paths they once were. Geodesics have an infinite proliferation of possible branches, at the whim of sub-atomic indeterminism.

Still, of course, in large masses the statistical results of the new physics are not much different from those given by the classical laws. But there is a fundamental difference. The apparent reality of the universe is the same—but it rests upon a quicksand of possible change.

Novel

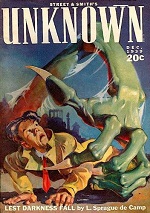

Lest Darkness Fall

- by L. Sprague de Camp

- in Unknown, December 1939

During a thunderstorm, archaeologist Martin Padway is thrown back to Rome of 535 A.D., whereupon he sets out to stop the coming Dark Ages.

Padway feared a mob of religious enthusiasts more than anything on earth, no doubt because their mental processes were so utterly alien to his own.

Novel

Short Story

El jardin de senderos que se bifurcan

- by Jorge Luís Borges

- in El jardin de senderos que se bifurcan, (Sur, 1941)

Short Story

Elsewhere

- by Robert A. Heinlein

- Astounding, September 1941

Professor Arthur Frost has a small but willing class of students who explore elsewhere and elsewhen.

Most people think of time as a track that they run on from birth to death as inexorably as a train follows its rails—they feel instinctively that time follows a straight line, the past lying behind, the future lying in front. Now I have reason to believe—to know—that time is analogous to a surface rather than a line, and a rolling hilly surface at that. Think of this track we follow over the surface of time as a winding road cut through hills. Every little way the road branches and the branches follow side canyons. At these branches the crucial decisions of your life take place. You can turn right or left into entirely different futures. Occasionally there is a switchback where one can scramble up or down a bank and skip over a few thousand or million years—if you don’t have your eyes so fixed on the road that you miss the short cut.

Short Story

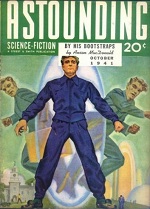

By His Bootstraps

- by Robert A. Heinlein

- Astounding, October 1941

Bob Wilson, Ph.D. student, throws himself 30,000 years into the future, where he tries to figure out what began this whole adventure.

Evan Zweifel gave me a copy of this magazine as a present!

Evan Zweifel gave me a copy of this magazine as a present!

Wait a minute now—he was under no compulsion. He was sure of that. Everything he did and said was the result of his own free will. Even if he didn’t remember the script, there were some things that he knew “Joe” hadn’t said. “Mary had a little lamb,” for example. He would recite a nursery rhyme and get off this damned repetitive treadmill. He opened his mouth—

Short Story

Mimsy Were the Borogoves

- by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore

- Astounding, February 1943

A scientist in the far future sends back two boxes of educational toys to test his time machine. One is discovered by Charles Dodgson’s niece in the 19th century, and the other by two children in 1942.

This story was in the first book that I got from the SF Book Club in the summer of 1970, The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume 1 (edited by Robert Silverberg). I read and reread those stories until the book fell apart.

This story was in the first book that I got from the SF Book Club in the summer of 1970, The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume 1 (edited by Robert Silverberg). I read and reread those stories until the book fell apart.

Neither Paradine nor Jane guessed how much of an effect the contents of the time machine were having on the kids.

Short Story

As Never Was

- by P. Schuyler Miller

- Astounding, January 1944

One of the first inexplicable finds by archaeologists traveling to the future is the blue knife made of no known material brought back by Walter Toynbee who promptly dies, leaving it to his grandson to explain the origin of the knife.

I knew grandfather. He would go as far as his machine could take him. I had duplicated that. He would look around him for a promising site, get out his tools, and pitch in. Well, I could do that, too.

Feature Film

Time Flies

- by J. O. C. Orton, Ted Kavanagh, and Howard Irving Young, directed by Walter Forde

- (at movie theaters, UK, 8 May 1944)

After Susie Barton’s husband invested their nest egg in Time Ferry Services, Ltd., it appears that the only way she’ll ever get anything out of it is by giving a performance in Elizabethan times.

This is the earliest appearance of a time machine—the “Time Ball”—in film that we know of. And based on the name Time Ferry Services, Ltd, it may also be the earliest film mention of a time travel agency. —Michael Main

This is the earliest appearance of a time machine—the “Time Ball”—in film that we know of. And based on the name Time Ferry Services, Ltd, it may also be the earliest film mention of a time travel agency. —Michael Main

Normally, we drift with the current and travel downstream and into what we call the future. Now, if we equip our little boat with a motor, we can speed our passage downstream into the future or, breasting the current, travel upstream to view again those selfsame scenes that were passed by humanity ages ago.

Novel

Novelette

Vintage Season

- by Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore

- Astounding, September 1946

More and more strange people are appearing each day in and around Oliver Wilson’s home; the explanation from the euphoric redhead leads him to believe they are time travelers gathering for an important event. —Michael Main

Looking backward later, Oliver thought that in that moment, for the first time clearly, he began to suspect the truth. But he had no time to ponder it, for after the brief instant of enmity the three people from—elsewhere—began to speak all at once, as if in a belated attempt to cover something they did not want noticed.

Novelette

Short Story

Brooklyn Project

- by William Tenn

- in Planet Stories, Fall 1948

So far, this is the earliest story I’ve read with the thought that a minuscule change in the past can cause major changes to our time. The setting is a press conference where the Secretary of Security presents the time-travel device to twelve reporters.

The traitorous Shayson and his illegal federation extended this hypothesis to include much more detailed and minor acts such as shifting a molecule of hydrogen that in our past really was never shifted.

Feature Film

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court

- by Edmund Beloin, directed by Tay Garnett

- (premiered at an unknown movie theater, New York City, 7 April 1949)

Bing Cosby’s delightful portrayal of the Yankee Hank Martin (why not Morgan?!) begins in 1912 after he’s already returned from Camelot. He’s just traveled to England and sought out the very castle of his 6th-century musical adventures, where he proceeds to tell his story to the master of the castle.

Based on Hank’s knowledge of the castle and its displays, the time travel definitely occurred in this version, with both the travel back and travel forward caused by clonks on the head. And based on the ending, Hank might not have been the only traveler through time. —Michael Main

Based on Hank’s knowledge of the castle and its displays, the time travel definitely occurred in this version, with both the travel back and travel forward caused by clonks on the head. And based on the ending, Hank might not have been the only traveler through time. —Michael Main

Docent: Kindly notice the round hole in the breastplate, undoubtedly caused by an iron-tipped arrow of the period.

Hank Martin: [shakes head and grunts] . . . I mean, well, that happens to be a bullet hole.

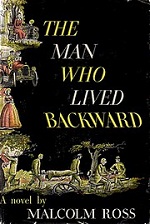

Novel

The Man Who Lived Backward

- by Malcolm Ross

- (Farrar Straus, 1950)

Mark Selby, born in June of 1940, achieves a unique perspective on life and war and death due to the fact that he lives each day from morning to night, aging in the usual way, but the next morning he wakes up on the previous day until he eventually dies just after (or is it before?) Lincoln’s assassination.

Tomorrow, my tomorrow, is the day of the President’s death.

Short Story

Time’s Arrow

- by Arthur C. Clarke

- in Science-Fantasy, Summer 1950

Barton and Davis, assistants to Professor Fowler, are on an archaeological dig when a physicist sets up camp next door and speculations abound about viewing into the past—or is it only viewing? —Michael Main

The discovery of negative entropy introduces quite new and revolutionary conceptions into our picture of the physical world.

Short Story

The Fox and the Forest

- by Ray Bradbury

- in Collier’s, 13 May 1950

Roger Kristen and his wife decide to take a time-travel vacation and then run so they’ll never have to return to the war torn world of 2155 AD.

The inhabitants of the future resent you two hiding on a tropical isle, as it were, while they drop off the cliff into hell. Death loves death, not life. Dying people love to know that others die with them. It is a comfort to learn you are not alone in the kiln, in the grave. I am the guardian of their collective resentment against you two.

Short Story

The Little Black Bag

- by C. M. Kornbluth

- Astounding, July 1950

In a 25th century where the vast majority of people have stunted intelligence (or at least talk with poor grammar), a physicist accidentally sends a medical bag back through time to Dr. Bayard Full, a down-on-his-luck, generally drunk, always callously self-absorbed, dog-kicking shyster. Despite falling in with a guttersnipe of a girl, Annie Aquella, he tries to make good use of the gift.

Switch is right. It was about time travel. What we call travel through time. So I took the tube numbers he gave me and I put them into the circuit-builder; I set it for ‘series’ and there it is-my time-traveling machine. It travels things through time real good.

Novel

Time and Again

- by Clifford D. Simak

- in Galaxy, October to December 1950 [3-part serial]

After twenty years, Ash Sutton returns in a cracked-up ship without food, air or water—only to report that the mysterious planet that nobody can visit is no threat to Earth. But a man from the future insists that Sutton must be killed to stop a war in time; while Sutton himself, who has developed metaphysical, religious leanings, finds a copy of This Is Destiny, the very book that he is planning to write.

It would reach back to win its battles. It would strike at points in time and space which would not even know that thre was a war. It could, logically, go back to the silver mines of Athens, to the horse and chariot of Thutmosis III, to the sailing of Columbus.

Short Story

Short Story

. . . and It Comes Out Here

- by Lester del Rey

- in Galaxy, February 1951

Old Jerome Boell, inventor of the household atomic power unit, visits his young self to make sure that the household atomic power unit gets invented, so to speak.

But it’s a longish story, and you might as well let me in. You will, you know, so why quibble about it? At least, you always have—or do—or will. I don’t know, verbs get all mixed up. We don’t have the right attitude toward tenses for a situation like this.

Short Story

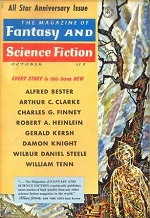

Of Time and Third Avenue

- by Alfred Bester

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, October 1951

Apparently, time travel has rules. For example, you cannot go back and simply take something from the past—it must be given to you. Thus, our man from the future must talk young Oliver Wilson Knight and his girlfriend into giving up the 1990 almanac that they bought in 1950.

If there was such a thing as a 1990 almanac, and if it was in that package, wild horses couldn’t get it away from me.

Novel

Short Story

A Sound of Thunder

- by Ray Bradbury

- in Collier’s, 28 June 1952

Eckels, a wealthy hunter, is one of three hunters on a prehistoric hunt for T. Rex conducted by Time Safari, Inc.

This was not the first speculation on small changes in the past causing big changes now (for example, Tenn’s “Me, Myself, and I”), but I wonder whether this was the first time that sensitive dependence on initial conditions was expressed in terms of a single butterfly.

This was not the first speculation on small changes in the past causing big changes now (for example, Tenn’s “Me, Myself, and I”), but I wonder whether this was the first time that sensitive dependence on initial conditions was expressed in terms of a single butterfly.

Not a little thing like that! Not a butterfly!

Short Story

All the Time in the World

- by Arthur C. Clarke

- Startling Stories, July 1952

Robert Ashton is offered a huge amount of money to carry out a foolproof plan of robbing the British Museum of its most valuable holdings. —Michael Main

Your time scale has been altered. A minute in the outer world would be a year in this room.

Short Story

Bring the Jubilee

- by Ward Moore

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, November 1952

In a world where the South won the “War for Southern Independence,” Hodge Backmaker, a northern country bumpkin with academic leanings, makes his way to New York City where he becomes disillusioned, ponders the notions of time and free will, and eventually goes to a communal think-tank where time travel offers him the chance to visit the key Gettysburg battle of the war.

I could say that time is an illusion and that all events occur simultaneously.

Short Story

Novelette

Short Story

Who’s Cribbing?

- by Jack Lewis

- Startling Stories, January 1953

Jack Lewis finds that all his story submissions are being returned to him with accusations of plagiarizing the great, late Todd Thromberry, but Lewis has another explanation.

Dear Mr. Lewis,

We think you should consult a psychiatrist.

Sincerely,

Doyle P. Gates

Science Fiction Editor

Deep Space Magazine

Short Story

Time Bum

- by C. M. Kornbluth

- Fantastic January/February 1953

After a con man reads a lurid science fiction magazine, a man who’s quite apparently out-of-time shows up to rent a furnished bungalow from Walter Lacblan.

Esperanto isn’t anywhere. It’s an artificial language. I played around with it a little once. It was supposed to end war and all sorts of things. Some people called it the language of the future.

Short Story

Short Story

Common Time

- by James Blish

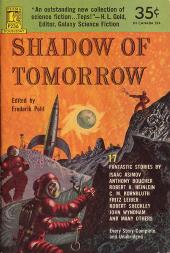

- in Shadow of Tomorrow, edited by Frederik Pohl (Permabooks, July 1953)

Spaceman Garrard is the third pilot to attempt the trip to the binary star system of Alpha Centauri using the FTL drive invented by Dolph Haertel (the next Einstein!) The Haertel Complex stories provide little in the way of actual time travel, but this one does have minor relativistic time dilation and more significant differing time rates. —Michael Main

Figuring backward brought him quickly to the equivalence he wanted: one second in ship time was two hours in Garrard time.

Novelette

Novelette

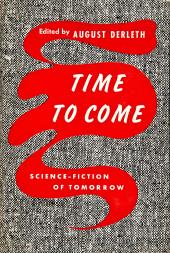

Jon’s World

- by Philip K. Dick

- in Time to Come: Science-Fiction Stories of Tomorrow, edited by August Derleth; Farrar (Strass and Young, April 1954)

First the Soviets and the Westerners fought. Then the Westerners brought Schonerman’s killer robots into the mix. Then the robots fought both human sides. You know all that from Dick’s earlier story, “Second Variety.” But now it’s long after the desolation, long enough that Caleb Ryan and his financial backer Kastner are willing to bring back the secret of Schonerman’s robots from the past to make their world a better place for surviving mankind, including Ryan’s visionary son Jon. —Michael Main

And then the

terminator’sclaws began to manufacture their own varieties and attack Soviets and Westerners alike. The only humans that survived were those at the UN base on Luna.

Short Story

Short Story

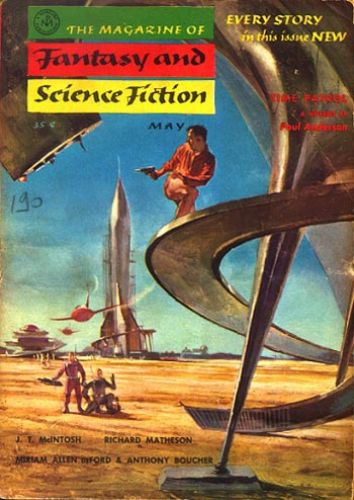

Time Patrol

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, May 1955

Former military engineer Manse Everard is recruited by the Time Patrol to prevent time travelers from making major changes to history (history bounces back from the small stuff).

For me, the logic of these stories pushes in a good direction, but still leaves one gaping hole that’s evinced by the fate of Manse’s compatriot Keith Denison in “Brave to Be a King”—namely, what happened to the younger Denison? Perhaps my problem is simply that I don’t grok ℵℵ-valued logic.

The stories have been collected in various volumes, the most complete of which is the 2006 Time Patrol that contains all but The Shield of Time.

For me, the logic of these stories pushes in a good direction, but still leaves one gaping hole that’s evinced by the fate of Manse’s compatriot Keith Denison in “Brave to Be a King”—namely, what happened to the younger Denison? Perhaps my problem is simply that I don’t grok ℵℵ-valued logic.

The stories have been collected in various volumes, the most complete of which is the 2006 Time Patrol that contains all but The Shield of Time.

If you went back to, I would guess, 1946, and worked to prevent your parents’ marriage in 1947, you would still have existed in that year; you would not go out of existence just because you had influenced events. The same would apply even if you had only been in 1946 one microsecond before shooting the man who would otherwise have become your father.

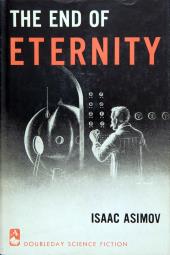

Novel

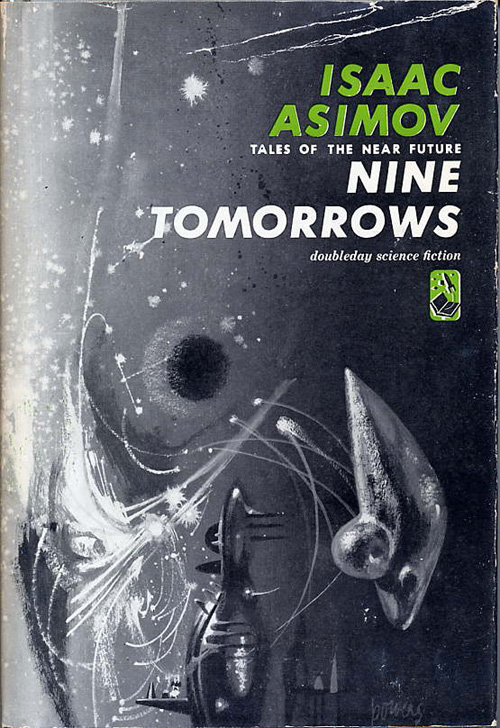

The End of Eternity

- by Isaac Asimov

- (Doubleday, August 1955)

Andrew Harlan, Technician in the everwhen of Eternity, falls in love and starts a chain of events that could lead to the end of everything. —Michael Main

He had boarded the kettle in the 575th Century, the base of operations assigned to him two years earlier. At the time the 575th had been the farthest upwhen he had ever traveled. Now he was moving upwhen to the 2456th Century.

Feature Film

Cesta do pravěku

- by J.A. Novotný and Karel Zeman, directed by Karel Zeman

- (at theaters, Czechoslovakia, 5 August 1955)

Novelette

Delenda Est

- by Poul Anderson

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, December 1955

Events are the result of a complex. There are no single causes. That’s why it’s so hard to change history. If I went back to, say, the Middle Ages, and shot one of FDR’s Dutch forebears, he’ll still be born in the late nineteenth century—because he and his genes resulted fom the entire world of his ancestors, and there’d have been compensation. But evey so often, a really key event does occur. Some one happening is a nexus of so many world lines that its outcome is decisive for the whole future.

Short Story

A Gun for Dinosaur

- by L. Sprague de Camp

- in Galaxy, March 1956

Dinosaur hunter Reggie Rivers and his partner, the Raja, organize time-travel safaris in a world with a Hawking-style chronological protection principle.

Oh, I’m no four-dimensional thinker; but, as I understand it, if people could go back to a more recent time, their actions would affect our own history, which would be a paradox or contradiction of facts. Can’t have that in a well-run universe, you know.

Feature Film

Novelette

Short Story

The Failed Men

- by Brian Aldiss

- in Science Fantasy, May 1956

Surry Edmark, a 24th century volunteer on a humanitarian mission to save mankind from extinction some 360,000 centuries in the future, tells his story to a comforting young Chinese woman.

You are the struback.

Short Story

Absolutely Inflexible

- by Robert Silverberg

- Fantastic Universe, July 1956

Whenever one-way jumpers from the past show up, it’s up to Mahler to shuffle them off to the moon where they won’t present any danger of infection to the rest of humanity, but now Mahler is faced with a two-way jumper.

Even a cold, a common cold, would wipe out millions now. Resistance to disease has simply vanished over the past two centuries; it isn’t needed, with all diseases conquered. But you time-travelers show up loaded with potentialities for all the diseases the world used to have. And we can’t risk having you stay here with them.

Short Story

Compounded Interest

- by Mack Reynolds

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, August 1956

“Mr. Smith” shows up in 1300 A.D. to invest ten gold coins at 10% annual interest with Sior Marin Goldini’s firm, after which he shows up every 100 years to provide guidance.

In one hundred years, at ten per cent compounded annually, your gold would be worth better than 700,000 zecchini.

Short Story

Novel

Novel

The Door Into Summer

- by Robert A. Heinlein

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Oct-Dec 1956

Inventor Dan Davis falls into bad company and wakes up 30 years later, but he gets an idea of how to put things right even at this late point.

Denver in 1970 was a very quaint place with a fine old-fashioned flavor; I became very fond of it. It was nothing like the slick New Plan maze it had been (or would be) when I had arrived (or would arrive) there from Yuma; it still had less than two million people, there were still buses and other vehicular traffic in the streets—there were still streets; I had no trouble finding Colfax Avenue.

Novel

Short Story

Novel

Novel

Novel

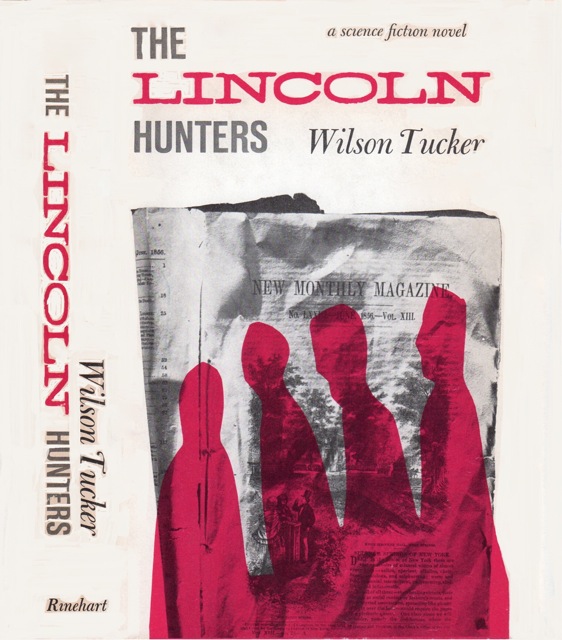

The Lincoln Hunters

- by Wilson Tucker

- (Rinehart, 1958)

When a time travel novel brags the title The Lincoln Hunters, you more-or-less expect a mad race to stop John Wilkes Booth, but Tucker’s book instead focuses on Benjamin Steward, an agent of Time Researchers who is pegged to lead a team from the year 2578 back to 1856 Bloomington, Illinois, where they plan to record Lincoln’s lost speech condemning slavery.

Full of fire and energy and force; it was logic; it was pathos; it was enthusiasm; it was justice, equity, truth and right, the good set ablaze by the divine fires of a soul maddened by the wrong; it was hard, heavy, knotty, gnarled, edged and heated, backed with wrath.

Novel

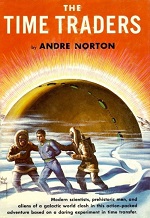

The Time Traders

- by Andre Norton

- (World Publishing Co., 1958)

Young Ross Murdock, on the streets and getting by with petty crime and quick feet, gets nabbed and sent to a secret project near the north pole—the first of many secret projects for the Time Traders series.

So they have not briefed you? Well, a run is a little jaunt back into history—not nice comfortable history such as you learned out of a book when you were a little kid. No, you are dropped back into some savage time before history—

Feature Film

Terror from the Year 5,000

- written and directed by Robert J. Gurney, Jr.

- (at theaters, January 1958October

Novel

Short Story

The Ugly Little Boy

- by Isaac Asimov

- (Galaxy Science Fiction, September 1958, pp. 6-44.)

Edith Fellowes is hired to look after young Timmie, a Neanderthal boy brought from the past, but never able to leave the time stasis bubble where he lives.

He was a very ugly little boy and Edith Fellowes loved him dearly.

Short Story

The Men Who Murdered Mohammed

- by Alfred Bester

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, October 1958

When Professor Henry Hassel discovers his wife in the arms of another man, he does what any mad scientist would do: build a time machine to go back and kill his wife’s grandfather. He has no trouble changing the past, but any effect on the present seems rather harder to achieve.

“While I was backing up, I inadvertently trampled and killed a small Pleistocene insect.”

“Aha!” said Hassel.

“I was terrified by the indicent. I had visions of returning to my world to find it completely changed as a result of this single death. Imagine my surprise when I returned to my world to find that nothing had changed!”

Short Story

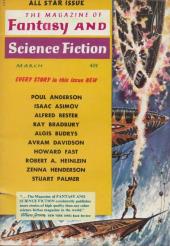

“—All You Zombies—”

- by Robert A. Heinlein

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, March 1959

A 25-year-old man, originally born as an orphan girl named Jane, tells his story to a 55-year-old bartender who then recruits him for a time-travel adventure. —Michael Main

When I opened you, I found a mess. I sent for the Chief of Surgery while I got the baby out, then we held a consultation with you on the table—and worked for hours to salvage what we could. You had two full sets of organs, both immature, but with the female set well enough developed for you to have a baby. They could never be any use to you again, so we took them out and rearranged things so that you can develop properly as a man.

Novelette

Brave to Be a King

- by Poul Anderson

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, August 1959

Patrolman Keith Denison uses some sketchy tactics (sketchy to the Patrol, that is) to track down his partner Keith Denison, who’s disappeared in the time of the Persian King Cyrus the Great, —Michael Main

In the case of a missing man, you were not required to search for him just because a record somewhere said you had done so. But how else would you stand a chance of finding him? You might possibly go back and thereby change events so that you did find him after all—in which case the report you filed would “always” have recorded your success, and you alone would know the “former” truth.

Novel

TV Episode

Walking Distance

- by Rod Serling, directed by Robert Stevens

- (CBS-TV, USA, 30 October 1959)

Stopped at a gas station outside of his boyhood hometown, burnt-out executive Martin Sloan decides to explore the town, which surprisingly has not changed at all in twenty-some years. —Michael Main

I know you’ve come from a long way from here . . . a long way and a long time.

Novelette

The Only Game in Town

- by Poul Anderson

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, January 1960

While on a two-man mission to stop a Mongol party from exploring North America in AD 1280, Patrolman John Sandoval gets a cracked skull, which leaves Manse Everard to figure out a way to save John and the mission while waxing philosophical about time travel and the Time Patrol. —Michael Main

Thin lightnings winked from above. The cloven air boomed behind them. He felt a chill, deeper than the night cold. But he eased his pace. There was no more reason for hurry.

Novelette

The Only Game in Town

- by Poul Anderson

- Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, January 1960

While on a two-man mission to stop a Mongol party from exploring North America in AD 1280, Patrolman John Sandoval gets a cracked skull, which leaves Manse Everard to figure out a way to save John and the mission while waxing philosophical about time travel and the Time Patrol. —Michael Main

Thin lightnings winked from above. The cloven air boomed behind them. He felt a chill, deeper than the night cold. But he eased his pace. There was no more reason for hurry.

TV Episode

Execution

- by Rod Serling, directed by David Orrick McDearmon

- (CBS-TV, USA, 1 April 1960)

Back in the 1880s, just after a man without conscience is dropped from a lone tree with a rope around his neck, a scientist pulls him into 20th-century New York City.

Serling wrote this script based on a George Clayton Johnson’s bare bones, present-tense treatment for a TV script, complete with an indication of where the commercial break should go. For this episode, Serling filled in the flesh and cut the fat from a bare bones, present-tense treatment by George Clayton Johnson. The treatment appeared in Johnson’s 1977 retrospective collection of scripts and stories, and in Volume 9 of Serling’s collected Twilight Zone scripts, Johnson commented that “Rod took my idea and went off to the races with it. He had a remarkable knowledge of what would and wouldn’t work on television, and he took everything that wouldn’t work out of ‘Execution’. He worked like a surgeon; a little snip here, a complete amputation over there, move this bone into place, graft over that one. When he was done, my little story had grown into a television script that lived and breathed on its own.” Serling also added a nice twist at the end that, for us, warranted the TV episode an Eloi Honorable Mention.

Rod Serling wrote this script based on a 1960 Twilight Zone episode of the same name, but I’m uncertain whether the story was published before Johnson’s 1977 retrospective collection. —Michael Main

Serling wrote this script based on a George Clayton Johnson’s bare bones, present-tense treatment for a TV script, complete with an indication of where the commercial break should go. For this episode, Serling filled in the flesh and cut the fat from a bare bones, present-tense treatment by George Clayton Johnson. The treatment appeared in Johnson’s 1977 retrospective collection of scripts and stories, and in Volume 9 of Serling’s collected Twilight Zone scripts, Johnson commented that “Rod took my idea and went off to the races with it. He had a remarkable knowledge of what would and wouldn’t work on television, and he took everything that wouldn’t work out of ‘Execution’. He worked like a surgeon; a little snip here, a complete amputation over there, move this bone into place, graft over that one. When he was done, my little story had grown into a television script that lived and breathed on its own.” Serling also added a nice twist at the end that, for us, warranted the TV episode an Eloi Honorable Mention.

Rod Serling wrote this script based on a 1960 Twilight Zone episode of the same name, but I’m uncertain whether the story was published before Johnson’s 1977 retrospective collection. —Michael Main

Caswell: I wanna see if there are things out there like you described to me. Carriages without horses and the buildings that rise to—

Professor Manion: They’re out there, Caswell. . . . Things you can’t imagine.

Feature Film

The Time Machine

- by David Duncan, directed by George Pal

- (at limited movie theaters, Rome, 25 May 1960)

The Traveller now has a name—H. George Wells (played by Rod Taylor)—and Weena has the beautiful face and talent of Yvette Mimieux. —Michael Main

When I speak of time, I’m speaking of the fourth dimension.

Feature Film

Beyond the Time Barrier

- by Arthur C. Pierce, directed by Edgar G. Ulmer

- (at movie theaters, USA, circa July 1960)

Major Bill Allison flies the experimental X-80 into the year 2024 where a plague has turned most humans into subhuman mutants and the rest are mostly deaf, dumb, and sterile. Once there, the leaders of an underground citadel (not to be confused with the ITTDB Citadel) have plans for him to marry the beautiful telepathic (and possibly non-sterile) Princess Trirene, and thereby re-populate the world. But together with Trirene and a small group of scientists, he devises a plan to return to his own time and prevent the plague from ever occurring.

The flight to the future is explained by scientific gibberish that contains a high concentration of mumbo jumbo, but the gist of it is that the speed of Allison’s plane (around 10,000 mph) added to the rotational speed of the Earth plus the speed of the Earth’s orbit around the sun plus the speed of the Solar System around the center of the galaxy plus maybe another speed or two, managed to bring his total speed close to that of light, which brought him to the future. Apparently, reversing his plane’s path is all that’s needed to return him to the past (ideally with Trirene beside him).

A self-defeating act paradox is set up nicely (if Alison stops the plague, then the citadel in the, future won’t be there to send him back to stop the plague), but the issue is never explicitly discussed and the ending of the film is inconclusive on the matter. Nevertheless, I commend the film for being the first to raise the issue of time travel paradoxes, albeit in the background. —Michael Main

The flight to the future is explained by scientific gibberish that contains a high concentration of mumbo jumbo, but the gist of it is that the speed of Allison’s plane (around 10,000 mph) added to the rotational speed of the Earth plus the speed of the Earth’s orbit around the sun plus the speed of the Solar System around the center of the galaxy plus maybe another speed or two, managed to bring his total speed close to that of light, which brought him to the future. Apparently, reversing his plane’s path is all that’s needed to return him to the past (ideally with Trirene beside him).

A self-defeating act paradox is set up nicely (if Alison stops the plague, then the citadel in the, future won’t be there to send him back to stop the plague), but the issue is never explicitly discussed and the ending of the film is inconclusive on the matter. Nevertheless, I commend the film for being the first to raise the issue of time travel paradoxes, albeit in the background. —Michael Main

I may be able to prevent it: Is that what you mean?

Novelette

The Six Fingers of Time

- by R. A. Lafferty

- If, September 1960

The story does not involve time travel, but it does have speeded-up time as in “The New Accelerator” by H. G. Wells. —Fred Galvin

I awoke this morning to some very puzzling incidents. It seemed that time itself had stopped, or that the whole world had gone into super-slow motion.

TV Episode

The Trouble with Templeton

- by E. Jack Neuman, directed by Buzz Kulik

- (CBS-TV, USA, 9 December 1960)

The trouble with aging actor Booth Templeton is that he sees life as useless even decades after his young wife died. The answer to his trouble may lie in the people he meets—including his dead wife, Laura!—in what appears to be his hangouts from some thirty years ago. Actual time travel or something more fantastical? You be the judge. —Michael Main

Laura! The freshest, most radiant creature God ever created. Eighteen when I married her, Marty, . . . twenty-five when she died.

TV Episode

A Most Unusual Camera

- by Rod Serling, directed by John Rich

- (CBS-TV, 16 December 1960)

Petty thieves Chet and Paula Diedrich are frustrated, angry, and in a bickering mood when they find nothing but cheap junk in the 400-lbs. of stuff they lifted from a curios store in the middle of the night, . . . until that boxy looking camera with the indecipherable label—dix à la propriétaire—produces a photo of the immediate future. —Michael Main

Yeah, it takes dopey pictures—dopey pictures like things that haven’t happened yet, but they do happen.

TV Episode

TV Episode

TV Episode

Short Story

The End

- by Fredric Brown

- in Dude, May 1961

I like Fredric Brown and his creative mind, but this was just a gimmick short short time-travel story in which the gimmick didn’t gimme anything. Now, if he had used this gimmick and the story had actually parsed, that would have caught my attention.

. . . run backward run. . .

Short Story

TV Episode

Novel

Novel

Short Story

Short Film

La jetée

- written and directed by Chris Marker

- (at movie theaters, France, 16 February 1962) [Accessed at Youtube on 28 February 2022.]

In a world made uninhabitable by the Third World War, a prisoner is chosen as being the only person with vivid enough memories of the past to travel through time and return with salvation.

This 28-minute photo montage with about 1,200 words of narration has a nice seed of an idea, but I find it insulting to other talented filmmakers that Time magazine ranked this sketch of a film as #1 in their 2010 list of best time travel movies. —Michael Main

This 28-minute photo montage with about 1,200 words of narration has a nice seed of an idea, but I find it insulting to other talented filmmakers that Time magazine ranked this sketch of a film as #1 in their 2010 list of best time travel movies. —Michael Main

Tel était le but des expériences : projeter dans le Temps des émissaires, appeler le passé et l’avenit au secours du présent.

translate

Such was the purpose of the experiments: to project emissaries into Time, to summon the Past and the Future to the aid of the Present.

Feature Film

Muz z prvního století

- written by Oldřich Lipský et al., directed by Oldrich Lipský

- (at theaters, Czechoslovakia, March 1962)

TV Episode

TV Episode

Of Late I Think of Cliffordsville

- by Rod Serling, directed by David Lowell Rich

- (CBS-TV, 11 April 1963)

TV Episode

The Incredible World of Horace Ford

- by Rod Serling, directed by Abner Biberman

- (CBS-TV, 18 April 1963)

Novel

The Great Time Machine Hoax

- by Keith Laumer

- in Fantastic Stories of Imagination, June to August 1963

When Chester W. Chester inherits an omniscient computer, he and his business partner Case Mulvihill arrange to promote the machine as if it were a time machine.

Now, this computer seems to be able to fake up just about any scene you want to take a look at. You name it, it sets it up. Chester, we’ve got the greatest side-show attraction in circus history! We book the public in at so much a head, and show ’em Daily Life in Ancient Rome, or Michelangelo sculpting the Pietà, or Napoleon leading the charge at Marengo.

TV Episode

TV Series

Dr. Who

- by Sydney Newman et al.

- (23 November 1963)

Sadly, I’ve never been a vassel of the Time Lord, though I’ve seen his pull on his other subjects such as my student Viktor who gave me a run-down of the TV and movie series and spin-offs. In exchange, I guaranteed him at least a 4-star rating and he promised to never again mention the short story, comic book, audio book, radio, cartoon, novel, t-shirt, stage and coffee mug spin-offs.

Hard to remember. Some time soon now, I think.

Short Story

La macchina che fermera il tempo

- by Dino Buzzati

- in Les 20 meilleurs récits de science-fiction, edited by Hubert Juin (Marabout, 1964)

Novel

TV Episode

Short Story

TV Episode

Short Story

TV Episode

Soldier

- by Harlan Ellison and Leslie Stevens, directed by Gerd Oswald

- (ABC-TV, USA 19 September 1964)

Feature Film

The Time Travelers

- written and directed by Ib Melchior

- (theatrical release, USA, 29 October 1964)

Using their time viewer, three scientists see a desolate landscape 107 years in the future, at which point the electrician realizes that the viewer has unexpectedly become a portal. All four jump through, only to have the portal collapse behind them, whereupon they are chased on the surface by Morlockish mutants who are afraid of thrown rocks, and they meet an advanced, post-apocalyptic, underground society that employs androids and is planning a generation-long trip to Alpha Centauri.

The film draws in at least four important additional time travel tropes: suspended animation, a single consistent timeline (with the corresponding inability to go back and change it), experiencing the passage of time at different rates, and a trip to the far future. And according to the SF Encyclopedia, the film was originally conceived as a sequel to the 1960 film of The Time Machine. —Michael Main

The film draws in at least four important additional time travel tropes: suspended animation, a single consistent timeline (with the corresponding inability to go back and change it), experiencing the passage of time at different rates, and a trip to the far future. And according to the SF Encyclopedia, the film was originally conceived as a sequel to the 1960 film of The Time Machine. —Michael Main

Isn’t it obvious? The war did happen. You never did go back with your warning.

Short Story

Short Story

Man in His Time

- by Brian Aldiss

- in Science Fantasy, April 1965

Janet Westerman is trying to cope with the return of her husband Jack from a mission to Mars in which some aspect of the planet made it so that his sensory input now comes from 3.3077 minutes in the future.

Dropping the letter, she held her head in her hands, closing her eyes as in the curved bone of her skull she heard all her possible courses of action jar together, future lifelines that annihilated each other.

Novel

The Corridors of Time

- by Poul Anderson

- in Amazing, May-Jun 1965

While awaiting trial for a self-defense killing, young Malcolm Lockridge is approached by a wealthy beauty, Storm Darroway, who offers to defend him in return for him joining her in what he eventually finds out are Wars in Time between the naturalist Wardens and the technocrat Rangers.

For many years, I thought this novel was part of Poul’s Time Patrol series, until Bob Hasse mentioned this as one of his favorites that is not in the series. The beginning reminded me of Heinlein’s Glory Road, and the rest is reminiscent of Asimov’s The End of Eternity, both of which captivated me in the summer of 1968. Poul’s book holds up well in that company.

For many years, I thought this novel was part of Poul’s Time Patrol series, until Bob Hasse mentioned this as one of his favorites that is not in the series. The beginning reminded me of Heinlein’s Glory Road, and the rest is reminiscent of Asimov’s The End of Eternity, both of which captivated me in the summer of 1968. Poul’s book holds up well in that company.

A series of parallel black lines, several inches apart, extended from it, some distance across the corridor floor. At the head of each was a brief inscription, in no alphabet he could recognize. But every ten feet or so a number was added. He saw 4950, 4951, 4952. . .

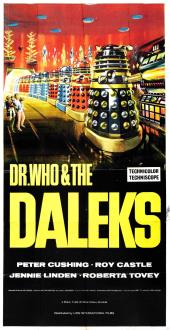

Feature Film

Doctor Who and the Daleks

- by Milton Subotsky, directed by Gordon Flemyng

- (unknown release details, 25 June 1965)

Novel

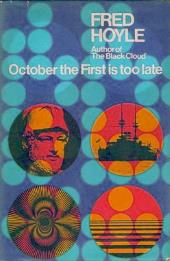

Novel

October the First Is Too Late

- by Fred Hoyle

- (William Heinemann, 1966)

Dick, a composer, and his boyhood friend John, now an eminent scientist, find themselves in a patchwork world of different times from classical Greece to a far future that humanity barely survives.

My favorable impression is no doubt reflective of the time when I read it (the summer of 1970, nearly 13, while moving from Washington State to Alabama). Perhaps the fiction doesn’t hold up as well decades later up, but the issues of time that it brings up still interest me and it was my first exposure to the idea of a geographic timeslip. And, similar to Asimov, Hoyle served to cultivate my interest in the natural sciences. —Michael Main

My favorable impression is no doubt reflective of the time when I read it (the summer of 1970, nearly 13, while moving from Washington State to Alabama). Perhaps the fiction doesn’t hold up as well decades later up, but the issues of time that it brings up still interest me and it was my first exposure to the idea of a geographic timeslip. And, similar to Asimov, Hoyle served to cultivate my interest in the natural sciences. —Michael Main

To the Reader: The “science” in this book is mostly scaffolding for the story, story-telling in the traditional sense. However, the discussions of the significance of time and the meaning of consciousness are intended to be quite serious, as also are the contents of chapter fourteen. —from Hoyle’s preface

Short Story

Short Story

Divine Madness

- by Roger Zelazny

- in Magazine of Horror, Summer 1966

A man has seizures that reverse small portions of his life that he must then relive.

The door slammed open.

Novel

Short Story

Light of Other Days

- by Bob Shaw

- Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact, August 1966

On a driving holiday in Argyll, Mr. and Mrs. Garland hope to find a way out of their hateful marriage, but instead they find a field of slow glass harvesting the light of other days. —Michael Main

Apart from its stupendous novelty value, the commercial success of slow glass was founded on the fact that having a scenedow was the exact emotional equivalent of owning land.

Feature Film

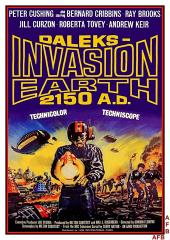

Daleks’ Invasion Earth 2150 A.D.

- by Milton Subotsky, directed by Gordon Flemyng

- (at movie theaters, UK, 5 August 1966)

Novella

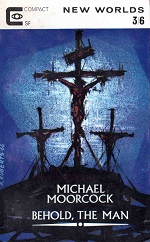

Behold the Man

- by Michael Moorcock

- New Worlds, September 1966

The first version of this story that I read was the 24-page graphic adaptation scripted by Doug Moench and illustrated by Alex Nino in final issue of my favorite comic magazine of 1975, the short-lived Unknown Worlds of Science Fiction. In the complex story, Karl Glogauer travels back to 28 A.D. hoping to meet Jesus, but none of the historical figures he meets are who he expected.

The Time Machine was a sphere full of milky fluid in which the traveller floated, enclosed in a rubber suit, breathing through a hose leading into the wall of the machine.

Feature Film

Feature Film

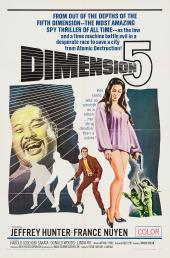

Dimension 5

- by Arthur C. Pierce, directed by Franklin Adreon

- (at movie theaters, USA, October 1966)

Justin Power, a 007-poser, has one thing that 007 never had: a spacetime belt with an eight-week time range forward or backward. As near as I can tell, going to the past rewinds time with only you retaining your memory. When you travel to the future, you just skip the intervening time and reappear at the same spot. And it seems you can also travel to nearby locations. I sure hope that Power and his sidekick Kitty can stop the H-bomb that’s being assembled in Los Angeles in the twenty film-minutes that are left after taking their time to set up the situation. —Michael Main

Power: [serious voice] One of the rules of time travel, Kitty, is to never kill anyone in the past, ’cause it might start a chain reaction that could indirectly affect your own life.

TV Episode

Tomorrow Is Yesterday

- by D. C. Fontana, directed by Michael O’Herlihy

- (NBC-TV, USA, 26 January 1967)

Darn those high-gravity black stars! Always accidentally throwing starships hither and yon through time. Although in this case, the crew of the Enterprise manages to correct all the problems they caused by beaming 1960s Air Force pilot Captain John Christopher on board. —Michael Main

Spock: Fifty years to go. Forty. Thirty.

Kirk: Never mind, Mr. Spock.

Spock: [silence]

Novel

Short Story

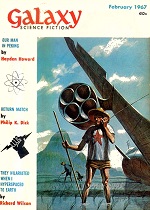

Thus We Frustrate Charlemagne

- by R. A. Lafferty

- in Galaxy, February 1967

The Ktistec machine Epiktistes and wise men of the world decide to change one moment in the dark ages while they carefully watch for changes in their own time.

We set out basic texts, and we take careful note of the world as it is. If the world changes, then the texts should change here before our eyes.

TV Episode

The City on the Edge of Forever

- by Harlan Ellison, directed by Joseph Pevney

- (NBC-TV, USA, 6 April 1967)

After a delirious Bones hurtles through a time portal to the 1930s, Kirk and Spock follow to save him and stop dangerous changes to the timeline, no matter the cost. —Michael Main

Novel

The Time Hoppers

- by Robert Silverberg

- (Doubleday, May 1967)

The High Government of the 25th century has directed Joe Quellen (a Level Seven) to find out who’s behind the escapes in time by lowly unemployed Level Fourteens and put a stop to it.

Suppose, he thought fretfully, some bureaucrat in Class Seven or Nine or thereabouts had gone ahead on his own authority, trying to win a quick uptwitch by dynamic action, and had rounded up a few known hoppers in advance of their departure. Thereby completely snarling the fabric of the time-line and irrevocably altering the past.

Short Story

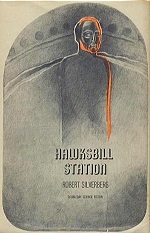

Hawksbill Station

- by Robert Silverberg

- in Galaxy, August 1967

Jim Barrett was one of the first political prisoners sent on a one-way journey to a world of rock and ocean in 2,000,000,000 BC; now a secretive new arrival threatens to upset the harsh world that he looks after.

One of his biggest problems here was keeping people from cracking up because there was too little privacy. Propinquity could be intolerable in a place like this.

Novel

An Age

- by Brian Aldiss

- serialized New Worlds, October to December 1967

Once again, here’s an example that’s not time travel. Instead, an artist named Edward Bush (and others) “mind travel” to the Jurassic (and other ages) where they may view the past without physically traveling. Viewing the past is not time travel. Interestingly, though, the authoritarian government can’t seem to get their hands on the travelers while they’re traveling, so I am gonna count this as time travel.

On his last mind into the Devonian, when this tragic illness was brewing, he had intercourse with a young woman called Ann.

Short Story

The Night That All Time Broke Out

- by Brian Aldiss

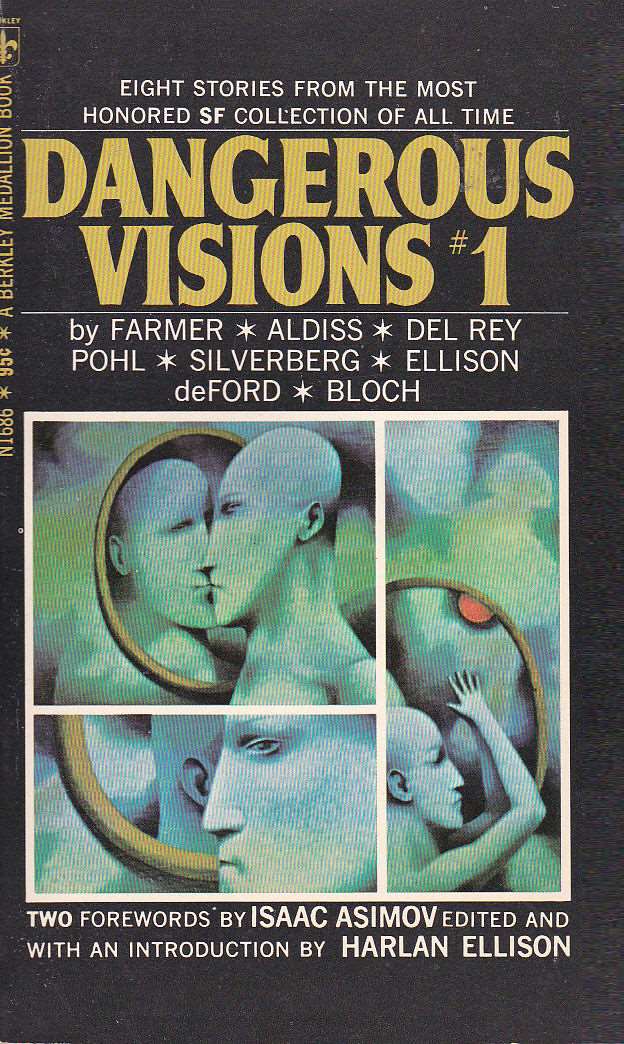

- in Dangerous Visions, edited by Harlan Ellison (Doubleday, October 1967)

Aldiss confessed that this story contains one of the wackiest ideas that he ever had. Does it contain time travel? You should read the story first and decide for yourself, but here’s my spoil-laden take on the matter: